The human gesture of illustration

Owen Smith and Michael Wertz reflect on the meaning and “poetry” of illustration, and its role during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond

We are giving you what we feel

As still and cloistered as we may feel these days, times are moving fast. Circumstances are tenuous, structures scrutinized, reactions flare, and we yearn to see and understand what is happening both within and beyond our own experience. The marks of other humans, in image and sound, are beacons of meaning-making that can help us navigate and name these complexities.

I find myself drawn to illustrations where the sincerity and efficiency sometimes outpace words. I sat down with Owen Smith and Michael Wertz, the chair and assistant chair of Illustration at CCA, and asked them why illustration has such power to connect. Wertz reflected that “there is a human touch that can make it feel like a gesture from one person to another.” Smith adds, “It’s not concrete, it can function like poetry. It sometimes removes the specificity of an individual or scene, and can be more about the gesture, the color, the psychological elements. The definition of illustration is often about making something clear, but that’s not always our intention; often we are giving you what we feel—less of a definition, more of an evocation. It becomes a sort of time capsule, a moment of feeling. Sometimes illustrated images act as propaganda, and some can be deeply problematic, but they do reflect some portion of the culture at a particular time.”

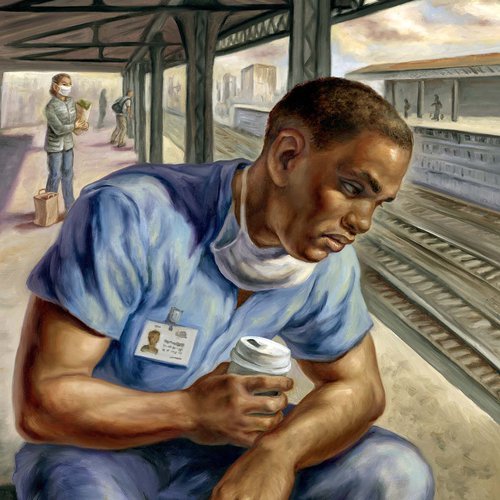

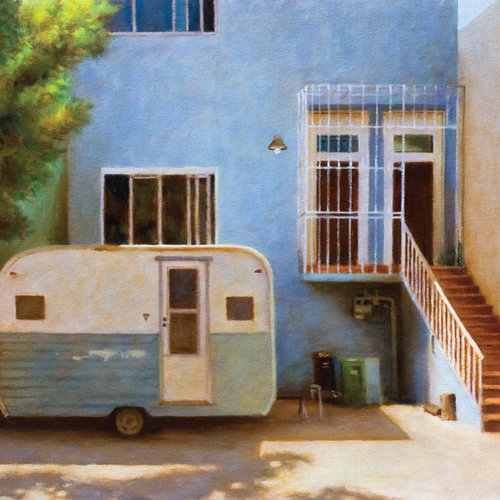

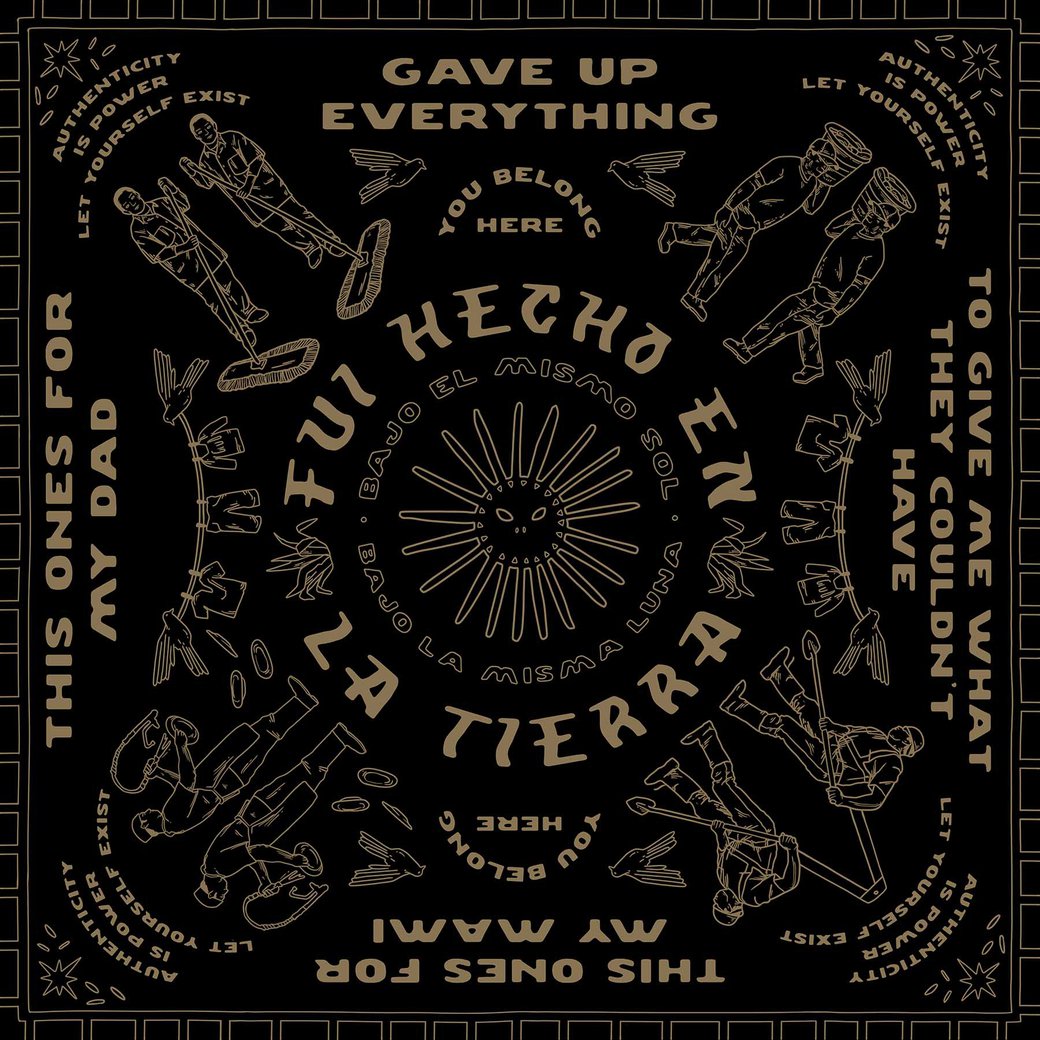

These capsules of feeling can be hauntingly true to our own life, as in Shrey Purohit’s painting from the “orange day,” when a marine layer of fog mixed with wildfire smoke to veil our city, casting shadow on people in camper vans and mansion dwellers alike. Or they can transport us to places we know and love, like the achingly familiar vignette of Smith’s New Yorker cover After the Shift. They can reveal a personal narrative, like Jessica Yeh’s raw self portrait of her mind running wild in the early morning on the toilet, or call us to action, like Wertz’s work with Lea Redmond on Vote! Vote! Vote!. Illustration can be part of unifying a movement, giving an efficient signal easily reproduced in living rooms, studios, and shops.

Illustration can document and reflect, it can tell us we are not alone in the feelings we hold, it can visualize the invisible. Dean of Design Helen Maria Nugent reminded us during graduation in spring of 2020 that it was illustrators who drew the coronavirus image, making concrete something so scary and abstract (Alissa Eckert and Dan Higgins at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). This is part of a long tradition where education and, especially, science have partnered with illustrators to elucidate—not unlike the way a stained glass window or illuminated manuscript built faith through narrative long before literacy was widespread. The vast set of contexts for illustration make it a good place for a nimble artist.

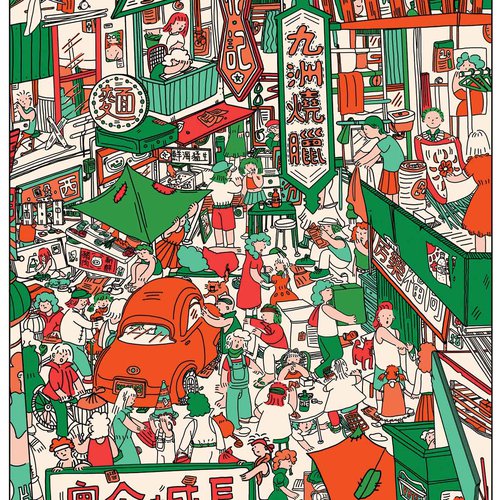

Valuing voice

Smith and Wertz have worked for years to build a program that positions students to embrace this breadth, with courses in hand lettering, sketchbook, surface design, kids books, comics, and more. Jasper Wong (BFA Illustration 2006), who spoke in the Design Lecture Series this October, embodies this range; his work spans concerts, gallery founding, sneakers, and murals. With breadth solidly woven into the curriculum, the program’s chairs are now shifting toward content and voice, with emphasis on personal, political, and social subjects, such as the Make It Queer studio, a broad course that engages LGBTQAI+ aesthetics and advocacy. They’re working to bring new faculty, who in turn bring new content. History courses, for example, are evolving to include the effect of images on culture over time, highlighting the marginalized voices that have been excluded. With an emphasis on the social nature of images comes important conversations about representation, where students ask—and also answer—what that can look like.

Paloma Diaz’s bandana design, honoring her immigrant parents, whose labor and dedication enabled her life and education.

Representation in fraught times

I asked Smith and Wertz how they talk through some of the problematic roles illustration has played in European colonialism, or how they broach subjects like Charlie Hebdo’s depictions of Muhammad. “It’s not our place to enlist students politically to our own beliefs, but we do encourage dialogue,” Smith says. “We’re always in a state of evolution, and that’s not always comfortable, but it is true to the experience of representing. It’s a good time for us to step back and listen.” As individuals, as teachers, as a community, we don’t always get it right. Wertz adds, “I see my part in the classroom as a facilitator. To let the group really get involved. Our hope is to not let it be one voice. We’re learning together, and making mistakes together.”

Ultimately what we need are more voices, and now is a promising time for that. “Though there is still a top-down struggle to get voices heard, there is this thing we used to laugh at called self-publishing,” Smith says, reflecting on the merits of this once-mocked opportunity. “We are less indebted to the corporate and publishing world, and it’s easier to get work out there, to find our audience, to not be stopped by print marketability. We can find the very specific people we want to talk to.”

Our students get both the opportunity and the difficulty of this time, and many are thriving, translating the ideas and feelings of now into powerful work. At the end of 2020, a moment when we were all excited to get some good news, CCA students were awarded 15 out of the 200 Society of Illustrators Student Scholarship Awards, with work ranging from wooden toys to book covers and paintings.

We need this work; for its call-outs, its humor, mirror, and sympathies. So much of it is about storytelling, and that can be a part of healing, a part of seeing each other. “We are all stuck in our little rooms,” says Wertz on teaching during the pandemic. “Maybe people are relying on images to help understand the world outside in a different way, understand somebody else’s point of view even. Storytelling can be key in making someone else’s view accessible.” Let’s receive this gift of view, and support this new generation of voices, helping us narrate and encapsulate our time. In their work we may see ourselves, but more important, we may see them.

—Saraleah Fordyce

December 15, 2020